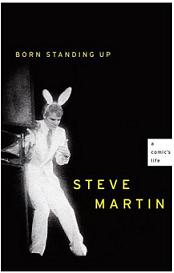

Born Standing Up

by Steve Martin

Scribner (November 20, 2007)

Tucker’s Rating: 6 / 10

[button link=”http://www.amazon.com/dp/1416553649/?tag=tuckermaxcom-20″ color=”blue” target=”blank” size=”large”]Buy on Amazon[/button]

[/grey_box]

What’s it about?: The autobiography of famous comedian, Steve Martin.

Tucker’s Opinion: This could and should have been such a good book, and it misses, and that sucks. It misses for one big reason: Steve refuses to really get into the meat of his emotional issues. He refuses to look at why he was so obsessed with comedy, how his painful childhood affected him and what that means to him even to this day. He admits to the pain and the suffering, really opens up about some of the awful things that happened to him, but he doesn’t go to the next step and really examine how it impacted him or the implications for his life. This is not a bullshit fluff celeb memoir, but you can tell that by this memoir that Steve doesn’t have anyone around him who will tell him the truth, to really make him sit down and look at the parts of his life he doesn’t want to look at. This frustrated me so much, because it’s obvious how smart and introspective Steve Martin is, but with most of the book, he doesn’t take that final step from introspection to actual realization.

That being said, there are some great lessons in this. The biggest one: Making it in anything, but especially the entertainment business, takes a shit load of practice and hard work. His struggle to the top is very interesting and should be read by all aspiring entertainers.

Notable Quotes (as marked by Tucker):

I did stand-up comedy for eighteen years. Ten of those years were spent learning, four years were spent refining, and four were spent in wild success.

I was seeking comic originality, and fame fell on me as a by-product. The course was more plodding than heroic: I did not strive valiantly against doubters but took incremental steps studded with a few intuitive leaps.

In spite of these sincere efforts at parenting, my father seemed to have a mysterious and growing anger toward me. He was increasingly volatile, and eventually, in my teens years, he fell into enraged silences. I knew that money issues plagued him and that we were always dependent on the next hypothetical real estate sale, and perhaps this was the source of his anger. But I suspect that as his show business dream slipped further into the sunset, he chose to blame his family who needed food, shelter, and attention. Though my sister seemed to escape his wrath, my mother grew more and more submissive to my father in order to avoid his temper. Timid and secretive, she whispered her thoughts to me with the caveat “Now, don’t tell anyone I said that,” filling me with a belief, which took years to correct, that it was dangerous to express one’s true opinion. Melinda, four years older than I, always went to a different school, and a sibling bond never coalesced until decades later, when she phoned me and said, “I want to know my brother,” initiating a lasting communication between us.

I was punished for my worst transgressions by spankings with a switch or a paddle, a holdover from any Texas childhood of that time, and when my mother warned, “Just wait til Glenn gets home,” I would be sick with fear, dreading nightfall, dreading the moment he would walk through the door. His growing moodiness made each episode of punishment more unpredictable — and hence, more frightening — and once, when I was about nine years old, he went too far. That evening, his mood was ominous as we indulged in a rare family treat, eating our Birds Eye frozen TV dinners in front of the television. My father muttered something to me, and I responded with a mumbled “What.” He shouted, “You heard me,” thundered up from his chair, pulled his belt out of its loops, and inflicted a beating that seemed never to end. I curled my arms around my body as he stood over me like a titan and delivered the blows. The next day I was covered in welts and wore long pants and sleeves to hide them at school. This was the only incident of its kind in our family. My father was never physically abusive toward my mother or sister and he was never again physically extreme with me. However, this beating and his worsening tendency to rages directed at my mother — which I heard in fright through the thin walls of our home — made me resolve, with icy determination, that only the most formal relationship would exist between my father and me, and for perhaps thirty years, neither he nor I did anything to repair the rift.

The rest of my childhood, we hardly spoke; there was little he said to me that was not critical, and there was little I said back that was not terse or mumbled. Wen I graduated from high school, he offered to buy me a tuxedo. I refused because I had learned from him to reject all aid and assistance; he detested extravagance and pleaded with us not to give him gifts. I felt, through a convoluted logic, that in my refusal, I was being a good son. I wish now that I had let him buy me a tuxedo., that I had let him be a dad. Having cut myself off from him, and by association the rest of the family, I was incurring psychological debts that would come due years later in the guise of romantic misconnections and a wrong-headed quest for solitude.

I have heard it said that a complicated childhood can lead to a life in the arts. I tell you this story of my family and me to let you know I am qualified to be a comedian.

All entertainment is or is about to become old-fashioned. There is room, he implies, for something new. To a young performer, this is a relief.

But the local folk clubs thrived on single acts, and, as usual, their Monday nights were reserved for budding talent. Stand-up comedy felt like an open door. It was possible to assemble a few minutes of material and be onstage that week, as opposed to standing in line in some mysterious world in Hollywood, getting no response, no phone calls returned, and no opportunity to perform. On Mondays, I could tour around Orange County, visit three clubs in one night, and be onstage, live, in front of an audience. If I flopped at the Paradox in Tustin, I might succeed an hour later at the Rouge et Noir. I found myself confining the magic to its own segment so I wouldn’t be called a magician. Even though the idea of doing comedy had sounded risky when I compared it to the safety of doing trick after trick, I wanted, needed, to be called a comedian. I discovered it was not magic I was interested in but performing in general. Why? Was I in a competition with my father? No, because I wasn’t aware of his interest in showbiz until years later. Was my ego out of control and looking for glory? I don’t think so; I am fundamentally shy and still feel slightly embarrassed at disproportionate attention. My answer to the question is simple: Who wouldn’t want to be in show business?

A skillful comedian could coax a laugh with tiny indicators such as a vocal tic (Bob Hopes “But I wanna tell ya”) or even a slight body shift. Jack E. Leonard used to punctuate jokes by slapping his stomach with his hand. One nigh, watching him on The Tonight Show, I noticed that several of his punch lines had been unintelligible, and the audience had actually laughed at nothing but the cue of his hand slap.

These notions stayed with me for months, until they formed an idea that revolutionized my comic direction: What if there were no punch lines? What if there were no indicators? What if I created tension and never released it? What if I headed for a climax, but all I delivered was an anticlimax. What would the audience do with all that tension? Theoretically, it would have to come out sometime. But if I kept denying them the formality of a punch line, the audience would eventually pick their own place to laugh, essentially out of desperation. This type of laugh seemed stronger to me, as they would be laughing at something they chose, rather than being told exactly when to laugh.

To test my idea, at my next appearance at the Ice House, I went onstage and began: “I’d like to open up with sort of a ‘funny bit of comedy.’ This has really been a big one for me…it’s the one that put me where I am today. I’m sure most of you will recognize the title when I mention it; it’s the Nose on Microphone routine [pause for imaged applause]. And it’s always funny, no matter how many times you see it.

I leaned in and placed my nose on the mike for a few long seconds. Then I stopped and took several bows, saying, “Thank you very much.” “That’s it?” they thought. Yes, that was it. The laugh came not then, but only after they realized I had already moved on to the next bit.

Now that I had assigned myself to an act without jokes, I gave myself a rule. Never let them know I was bombing: This is funny, you just haven’t gotten it yet. If I wasn’t offering punch lines, I’d never be standing there with egg on my face. It was essential that I never show doubt about what I was doing. I would move through my act without pausing for a laugh, as though everything were an aside. Eventually, I thought, the laughs would be playing catch-up to what I was doing. Either would be either delivered in passing, or the opposite, an elaborate presentation that climaxed in pointlessness. Another rule was to make the audience believe that I thought I was fantastic, that my confidence could not be shattered. They had to believe that I didn’t care if they laughed at all, and that this act was going on with or without them.

I was having trouble ending my show. I thought, “Why not make a virtue of it?” I started closing with extended bowing, as though I heard heavy applause. I kept insisting that I needed to “beg off.” No, nothing, not even this ovation I am imagining, can make me stay. My goal was to make the audience laugh but leave them unable to describe what it was that had made them laugh. In other words, like the helpless state of giddiness experienced by close friends turned in to each other’s sense of humor, you had to be there.

At least that was the theory. And for the next eight years, I rolled it up a hill like Sisyphus.

My first reviews came in. One said, “This so-called ‘comedian’ should be told that jokes are supposed to have punch lines.” Another said I represented “the most serious booking error in the history of Los Angeles music.”

“Wait,” I thought, “let me explain my theory!”

But guess what. There was a dark side. A regular conversation, except with established friends, became difficult, fraught with ulterior motives, and often degenerated into deadening nephew autograph requests. Almost every ordinary action that took place in public had a freakish celebrity aura around it. I would get laughs at innocuous things I said, such as “What time does the movie start?” or “Hello.” I would pull my hat down low on my head and stare at the ground when I walked through airports, and I would duck around corners quickly at museums. My room-service meal could be delivered by four people wearing arrows through their heads — funny, yes, but when you’re dead tired of your own jokes, it’s hard to respond with the expected glee. Cars would follow me recklessly on the freeway, and I worried for the passengers’ lives as the driver hung out the window, shouting, “I’m a wild a craaaazzzzyy guy!” while steering with one hand and holding a beer in the other. In a public situation, I was expected to be the figure I was onstage, which I stubbornly resisted. People were waiting for a show, but my show was only that, a show. It was precise and particular and not reproducible in a living room; in fact, to me my act was serious.

Fame suited me in that the icebreaking was already done and my natural shyness could be easily overcome. I was, however, ill suited for fame’s destruction of privacy, for the uninvited doorbell ringers and anonymous phone callers. I had never been outgoing, and when strangers approached me with the familiarity of old friends, I felt dishonest if I returned it in kind.

Time has helped me achieve peace with celebrity. At first I was not famous enough, then I was too famous, now I am famous just right. Oh yes, I have heard the argument that celebrities want fame when it’s useful and don’t when it’s not. That argument is absolutely true.

The Jerk, receiving one lone good review from a small paper in Florida and getting dismissive and sadistic reviews from the rest of the country, made one hundred eighty million dollars in old money. It was recently voted among the American Film Institute’s top one hundred comedies of all time, he said smugly. Because it was a hit, my life changed, though again, my father was not impressed. I had invited him to the premiere. the Bruin Theatre in Westwood, next to UCLA, was ringed outside with spotlights drawing figure eights in the sky and packed inside with clamoring, vocal fans. Press crews lined the red carpet, and it took us forty-five minutes to get from the car to our seats. The movie played well, and afterward my friends and I took my father to dinner at a quiet, old-fashioned eater that didn’t offer “silly” modern food. He said nothing about the film; he talked about everything but the film. Finally, one of my friends said, “Glenn, what did you think of Steve’s movie?” My father chuckled and said, “Well, he’s no Charlie Chaplin.”

My father’s health declined further, and he became bedridden. There must be an instinct about when the end is near; Melinda and I found ourselves at our parents’ home in Laguna Beach, California. I walked into the house they had lived in for thirty-five years, and my tearful sister said, “He’s saying goodbye to everyone.” A nurse said to me, “This is when it all happens.” I didn’t know what she meant, but I soon understood.

I was alone with him in the bedroom; his mind was alert but his body was failing. He said, almost buoyantly, “I’m ready now.” I sat on the edge of the bed, and another silence fell over us. Then he said, “I wish I could cry, I wish I could cry.”

At first I took this as a comment on his condition but am forever thankful that I pushed on. “What do you want to cry about?” I said.

“For all the love I received and couldn’t return.”

I felt a chill of familiarity.

There was another lengthly silence as we looked into each other’s eyes. At last he said, “You did everything I wanted to do.”

“I did it for you,” I said. Then we wept for the lost years. I was glad I didn’t say the more complicated truth: “I did it because of you.”